Fund-raising | en

Category : performances | Auff en

Fundraising

Please participate in the fundraising for Sarastro to make a self-funded performance of this opera possible! Add a translation into English

Category : performances | Auff en

Fundraising

Please participate in the fundraising for Sarastro to make a self-funded performance of this opera possible! Add a translation into English

Category : performances | Auff en

https://sammlungen.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/periodika/periodical/pageview/13384246

“Sarastro”.

We received a letter from Weimar about rehearsals of the new music drama of Karl Göpfart’s “Sarastro,” for which G. Stommel wrote the libretto using Goethe’s sequel to “The Magic Flute.” They were very well received this morning at a matinee held before a select audience. The entire performance was undertaken by local artists and the court opera singer Miss M. Recke from Berlin; the composer accompanied on the piano. The performance of the music drama requires first-rate vocal talents, particularly familiar with the Mozart school. In addition to the dramatic scenes, several of Goethe’s songs were performed from the collection of compositions of Goethe’s songs compiled by Max Friedländer (Berlin), which was published in the writings of the Goethe Society (1896). Some of these performances had a very unique charm, reminiscent of the time when grandfather took grandmother. The artistic success of the matinee was very favorable.

Category : performances | Auff en

Walter Dahms writes a detailed article about the opera in 1912.

[pgc_simply_gallery id=”221″]

The reason for no complete staged performance to date (still in 2026!) is described here:

When I first picked up the piano score of Goepfart’s “Sarastro,” I was shocked by the boldness of its creator to offer our time something so incredibly simple, clear, and unambiguous. True, this work was conceived and created for the Mozart anniversary in 1891. But the most unfortunate turmoil (especially the great printers’ strike) had prevented the planned performance – in Dresden and Prague – at that time. By the following year, it was already too late. Thus, “Sarastro” still lies unperformed [1912]. If it were up to the good Germans, who are so poorly informed about their creative artists by their favorite newspapers, the work could remain unperformed until the end of time. But it would be regrettable if the wall of inertia and malice that highly one-sided, self-serving journalism has erected between the creative minds and the gullible public could not be breached at some point. The attempt would be worthwhile, both instructive and promising.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Dahms

Hamburg Staatsbibliothek https://resolver.sub.uni-hamburg.de/kitodo/PPN774616555_0016

Karl Goepfart’s Music Drama “Sarastro”

By Walter Dahms

Who these days fails to prick up their ears when they hear of a work called “The Magic Flute, Part Two”? We talk and write so much about Mozart as the savior from today’s musical crisis, as the guide out of the desert of modern unproductivity. “Back to Mozart!” people cried. Weingartner said: “No, forward to Mozart!” Whatever one interprets it, one thing is certain: that a further development of the art of music-dramatics can never be a “going beyond Wagner,” but rather that the stage composer who wants to create something rare, lasting, and also new must start from a point before Wagner. For there are still many untrodden paths that lead to the goal of a great, sublime art.

When I first picked up the piano score of Goepfart’s “Sarastro,” I was shocked by the composer’s audacity in offering our time something so incredibly simple, clear, and unambiguous. True, this work was conceived and created for the Mozart anniversary in 1891. But the most unfortunate turmoil (above all, the great printers’ strike) had prevented the planned performance – in Dresden and Prague – at that time. Then, the following year, it was already too late. Thus, “Sarastro” still lies unperformed. If it were up to the good Germans, who are so poorly informed about their creative artists by their favorite newspapers, the work could remain unperformed forever. But it would be regrettable if the wall of inertia and malice that a highly one-sided, self-serving journalism has erected between the creative artists and the gullible public could not be breached at some point. The attempt would be worthwhile, both instructive and promising.

“Sarastro” made a deep, lasting impression on me upon my first acquaintance. I returned to the work again and again. My interest grew steadily. Here, finally, was a work that aimed for something completely different from what the modern world loves and promotes. Here, primal human emotions are not meant to disgust us (as with the popular verists and their German followers) – no, here they are meant to be refined. Something pure, down-to-earth, healthy – in short, something German speaks to us here in a powerful, sentimental, tearful bliss, like pathological outbursts, both verbal and musical. Therefore, I am now writing a warning for the work, because I have gained the firm, unshakable conviction as a musician and critic that it must also have an effect on every other person receptive to the noble.

The whole thing is symbolic – the struggle between light and darkness, between good and evil. Mozart’s “Magic Flute” also had this tendency. It was a protest, understandable to those in the know in Vienna at the time, against the indolent persistence, against the debauchery and enslavement of conscience in all areas. Without any humanitarian fanciness, it sought to proclaim the ideal of universal human brotherhood. (However, the French Revolution, which was just around the corner, imposed a shrill dissonance on this – also a kind of brotherhood, but a different one!). At that time, people wanted to portray characters purified by the trials of fate. Fire and water were merely symbols. The battle between light and darkness, between Sarastro and the Queen of the Night, is not played out in The Magic Flute, however. The finale points to the coming time, a time of struggle and strife.

No less a figure than Goethe planned and drafted a second part of The Magic Flute, the drama of Sarastro, as an operatic text. Goepfart’s work, whose poem was written by Gottfried Stommel, rests on this foundation. Goethe’s continuation of The Magic Flute was justified. The battle between the two hostile elemental forces, roughly embodied in light and darkness, had to be resolved at some point. Goethe’s outline provided the dramatic guidelines for Goepfart and Stommel. Mozart’s music had to be retained in certain melodies and motifs at certain points. And the outcome had to be conciliatory: love had to overcome hate. Equally necessary was the implementation of Masonic ideas through the conflict intended by Goethe. There can be no doubt about the legitimacy of Goethe’s continuation of The Magic Flute; one will affirm it unconditionally and joyfully once one has witnessed the fulfillment of its stated goals through the flawless execution of the Goepfart-Stommel work.

A consideration of “Sarastro” reveals that the acts, in their structure, carry a distinctive element of their essence. The first act contains the exposition. It introduces us to the various worlds of the drama: that of good (Sarastro), that of evil (Queen of the Night), and that of primitive humanity (Papageno). After the solemn introductory strains of The Magic Flute Overture, the curtain rises over the assembly of priests. Every year, they send one of their brothers into the world to witness the suffering and joy of humanity. The earthly pilgrim has returned pure, and this time his fate falls to Sarastro, their leader himself. He recognizes in this a special hint: “The deity tests in peril!” He knows that a grave, great mission awaits him. The old enemy, the Queen of the Night, the primordial evil, must be overcome. Only he is capable of doing this; for through his higher spiritual culture, he sees through her intentions, but she not his. A solemn, serious tone pervades this entire scene. Sustained rhythms, clear harmonies, and deeply soulful melodies permeate the music. It’s already clear here: “Sarastro” is a vocal opera in the same sense as Mozart’s operas. This also gives rise to the work’s special position in modern operatic literature. The orchestra doesn’t have the decisive say; it only provides the milieu, the ground, so to speak, on which the events (of a musical nature) unfold.

The first metamorphosis takes us into the realm of the Queen of the Night. A character portrait of a contrasting kind. Bouncing rhythms immediately convey a sense of the petty unrest that reigns in this realm. Like Sarastro, the Queen is shown to us in the midst of her comrades-in-arms. Monostatos, the Moor, whose daughter Pamina escaped in The Magic Flute and who now serves and loves his mother, reports to the queen that the work of revenge against the Kingdom of Light is in full swing. Tamino and Pamina’s child, the king’s son, lies locked in a golden coffin, the lid of which only their dark power can open. Symbolically: The new era is enslaved by the light-shy spirits. The queen’s triumphant howls reveal her inner opposition to the noble Sarastro. How just is his fight against her!

The second metamorphosis shows us Tamino and Pamina in parental concern for their darling. Tamino’s growing fears for his child result in a relapse into the spell of his mother, the Queen of the Night, who wishes to win him over to her work of revenge against Sarastro. But this proves to be a temptation for Sarastro, who consoles him with promises of the child’s great mission in the future. From the delicate lyricism of the women’s choir, whose singing accompanies the relentless carrying of the coffin, the music in the Temptation scene builds powerfully, leading to the magnificent, primal priestly chorus “Who will zeal against the light?”

The third metamorphosis presents us with the life and activities of the uninhibited natural people, embodied by Papageno and Papagena. Here, in the merry bustle of the children’s company, amidst joy and jest, the birth of Aurora takes place as a gift from the gods. She is the child of the people, destined to redeem the son of the princely house. Music of melodious serenity accompanies this metamorphosis. Several Mozartian melodies appear. The ebb and flow of life flows vividly, inexhaustibly, and with sure strokes, as simple as they are effective.

While the first act provided the exposition of the drama, the second achieves the climax of the dramatic effect with the exploding of the hostile forces. True to his divine calling, Sarastro is on his earthly journey. Here, he encounters his old enemy. The fate of the two elemental forces, light and darkness, is fulfilled. The queen does not recognize the wanderer. The spell of the unknown overwhelms her and causes her to burn with fierce love for him. She seeks to win him over to her own ends, all of which have Sarastro’s destruction as their underlying goal. He finally agrees to assist her in eliminating Sarastro when she vows to free Phoebus, the king’s son, from the golden coffin and thus restore him to life. Sarastro realizes that he must make sacrifices to overcome the queen and bring about the “new era.” The ethical power of his personality and his confessions is wonderful. Goepfart’s music is just as successful as the poet’s in constructing and executing this masterful act. He draws entirely from his own talent, and his source of melodic and characteristic invention is inexhaustible. With succinct strokes, he conveys the contrasts. His musical language is dramatically powerful and haunting, yet entirely unique and new. His confidence in expressing emotion is evident everywhere. Significant is how, in her apparent triumph, the Queen of the Night indulges in coloratura for the first time in the drama, as if out of inner necessity. Here, coloratura truly is a means of expression, a truly necessary and tension-relieving one.

The third act is uneven in its effect; this results from the accumulation of necessary resolutions. As a rare occurrence in dramatic literature, we find here that new characters (Aurora and Phoebus), who are significantly involved in the continuation and resolution of the conflicts, only appear in the third act. The third act naturally must primarily contain Mozartian motifs. Quoting Mozart is partly required by Goethe’s notes. Thus, Aurora appears with the glockenspiel music from “The Magic Flute.” This requires no justification; for here, no other notes could be heard than Mozart’s. Goepfart uses the musical rondo form in the individual numbers, which Mozart frequently employed. He had to stay within the style. Let it not be said that he made things simple and easy for himself by quoting Mozart’s music. On the contrary, it was an enormous difficulty to adapt his own sensibilities to Mozart’s style and spirit so as not to let the whole fall apart. He could have substituted his own invention for the quotations. But Mozart’s expression rightly seemed to him the only possible one at certain points.

The first scene takes us back to the primitive people in the forest. Here, Aurora performs the liberation of Phoebus and thus the reproduction of Promethean gods’ gift to humanity. The action builds to a deeply intimate love scene between the two symbolic figures. A burlesque scene, a panfest, if you will, follows, adorned with charming, distinctive ballet music.

The first metamorphosis shows us a piece of court life in Tamino’s royal palace. Ladies and gentlemen quarrel over the latest news. This fruitless argument is brought to an end by the announcement of the very latest news: the entry of the redeemed Prince Phoebus with Aurora. This marks the beginning of the end. A new era is born. Goepfart has found delightful tones for the courtiers’ conversation, tones that reveal him as a master of musical humor.

An open metamorphosis leads to the finale. Here, the most striking contrasts emerge between the joyful jubilation at the entry of the young princely couple and the grief of the priests over Sarastro’s death. These two scenes could only be portrayed with motifs inspired by Mozart: the jubilant chorus from The Magic Flute finale and the Fire and Water Music in C minor. As the action progresses, such as the intrusion of the Queen of the Night, who also appears for a victory and celebration, Goepfart has found his own, very characteristic accents. The action develops into a catastrophe. The queen demands to see her dead enemy: “and should my kingdom fall to ruins!” Tamino leads her to Sarastro’s sarcophagus. When she recognizes the wanderer in the corpse, she collapses unconscious. Meanwhile, “O Isis and Osiris” in Mozart’s immortal melody resounds from all the priests in unison, vowing to continue to work in Sarastro’s spirit even after his death. Overwhelmed by the terrible realization (of her own defeat) that has come to her, the queen expresses a passionate desire to enter into the sublime bond of love, but is indignantly rejected by the priests. In her anguish, the queen calls upon the transfigured Sarastro (her enemy and friend) to give her a sign of his reconciliation and the fulfillment of her wish. It happens. A genius appears, touches the queen with the palm of peace, and leads her into the realm of eternal peace. Sarastro and the queen appear united in the dome – love has overcome hate. Thus, all evils are erased. The ruling family and the people now join in the chorus of joy for liberation through love with a completely different elation.

Goepfart-Stommel’s “Sarastro” reveals itself as a work of ethical intent and pure, great will. That ability keeps pace with will can be clearly seen from the poetry and music. It is up to the German opera houses to ensure that such a serious and beautifully accomplished work does not fail to achieve success. It is your responsibility to bring to light a work that, in its lofty idea, in the simplicity and power of its conception and execution, stands out from the average, a work that, through its inner simplicity and truth, occupies an exceptional position in contemporary creation, and one that—I am firmly convinced—will always make a deep, lasting impression. The German stage, which begins with Goepfart’s “Sarastro,” will have the glory of a true artistic achievement.

Category : performances | Auff en

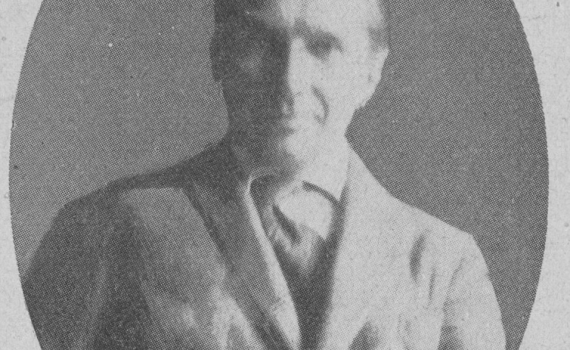

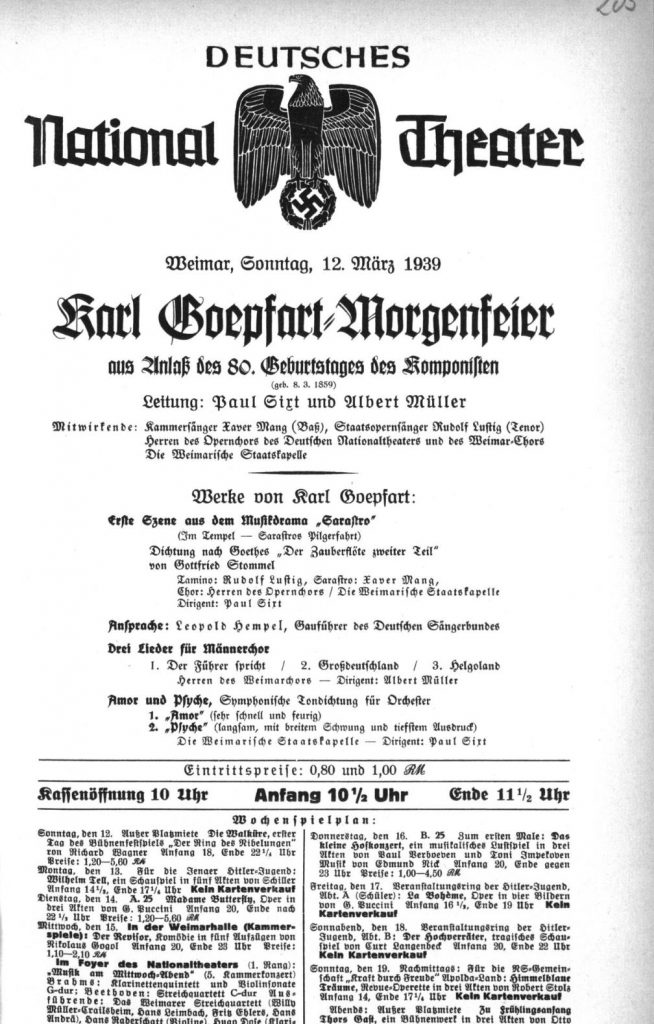

On 12th March1939 the first scene was performed to Goepfat´s 80th birthday in the German National Theatre Weimar.

Morgenfeier zum 80. Geburtstag

No other performances known.

Category : performances | Auff en

Google has scanned a piano reduction that is available for free download. Thank you!

One of the scores was initially untraceable.

The piano reduction was republished by the Ellenberger Institute in July 2024 and published on YouTube with a piano reduction in full performance.

Thanks to the discovery of the score in the Thuringian State Music Archive, the opera was first published on October 3, 2024.

Listen to the full performance!

Category : performances | Auff en

World Premiere 9th December 1891 concertante in Hengelo NL.

as I heard from the Schouwburg Hengelo director it must have been in the

Beursgebouw building which burnt down in 1921. It was built by architect Jacobus Moll.

Now there is the Schouwburg since 1913: https://www.schouwburghengelo.nl/

The history of the fire brigade in Hengelo

M. Zweerink

One of the most discussed major fires from Hengelo’s gray past is the devastating fire of the Beursgebouw in 1921. Attention has also been paid to this in this magazine.

The historic building was located on the corner of Beursstraat and the station square, where the ABN-AMRO bank is currently located. The name “Beursstraat” still reminds us of this building. By council decision of January 22, 1884, this street was called “Stationsweg”. The Stock Exchange building had already existed for 19 years and would only later give its name to this street.

We have to go back to 1865, the year in which the construction of this monumental building was initiated. In that year, the N.V. Twentsche Handels Sociëteit was founded. In those days, Hengelo became a center of railways serving lines from Enschede,

Oldenzaal, Almelo and Goor came together. This was the reason to build a building where cotton traders and manufacturers could meet and do business. The Dutch Trading Company provided strong assistance and the Stock Exchange building was built from a large stock exchange. The land price at that time was ƒ 1.25 per square meter. On April 25, 1867, the imposing building at that time was solemnly opened with a grand celebration speech by Mr. P. Vissering, professor in Leiden. The entrance with a bluestone staircase and several pillars, which formed a kind of loggia, increased the stateliness of the building. Despite the fact that it has a rich past, it never came into its own as a commercial building.

In the Stock Exchange building, in addition to the large hall, rooms were set up as a telegraph office, club and café and restaurant. Eminent speakers usually spoke before a packed room. Among them were Mr. Troelstra and the great Catholic leader Dr. Schaepman. Streets in Hengelo are named after both greats.

During the First World War (1914-1918) the building was used for a while as a residence for soldiers and internees.

But the Hengelo fire brigade also used the Beursgebouw at that time. It was during the time of “Spray I” and “Spray ll”.